The Science Was Never the Problem

What happened to STEM Toys before we noticed

Recently, I listened to an episode of STEM Conversations with Dame Chi Onwurah MP, Chair of the Science, Innovation and Technology Select Committee. She spoke about the gendered division of toys and the early signals this sends to children about who certain kinds of play, and by extension, certain futures, are for.

A blue-boxed robotics set. A pink-packaged knitting or “science for girls” kit. These design choices quietly communicate expectations not only to children but also to families. Over time, those cues shape who feels entitled to explore, enjoy, study, work, and lead in different areas.

As I listened, I found myself thinking back to my own childhood and to a question that has stayed with me since:

When do children start learning what kinds of thinking they are allowed to do?

A Christmas Present, Revisited

I grew up in Scotland in the 1980s and went on to become a scientist. As a young girl, imagining who I might become, I never felt that science was not for me. It entered my future career through library books and through skimming the Argos catalogue in the weeks leading up to Christmas.

In 1989, there was one thing at the top of my list to Santa: a chemistry set.

Years later, I realised I couldn’t clearly picture the box itself, only the ordered rows of small plastic tubes inside. Curious, I searched for an image online. Given the era, I expected the familiar caricature: a lone boy in safety goggles, hair askew, mid-gasp over a fizz, pop, or bang.

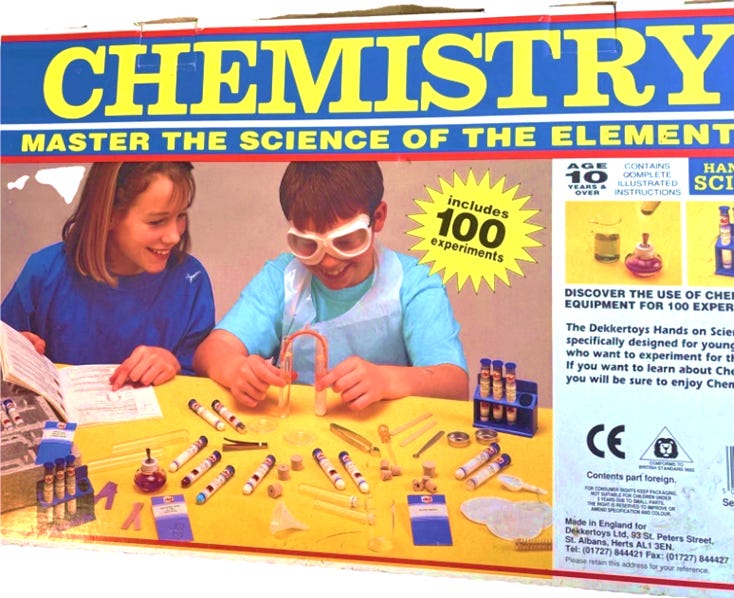

Instead, the box showed a boy and a girl working together. The boy was handling the equipment, while the girl read from the instructions, positioned not as a bystander but as someone potentially directing what happened next (Figure 1). No pink. No blue. No slogans about empowerment or special access. Just a promise to “Master the Science of the Elements.”

That moment gave me pause. Had I simply been lucky, or had something shifted since then?

Figure 1: My First Chemistry Set circa. 1989

A late-1980s chemistry kit showing a boy and a girl jointly engaged in experimental work.

Looking for Patterns, Not Nostalgia

I searched for vintage kids STEM kits, a slightly jarring reminder that the toys I played with are now classed as “vintage”. I gathered images from people selling old kits online: unopened, forgotten Christmas presents, rediscovered in attics.

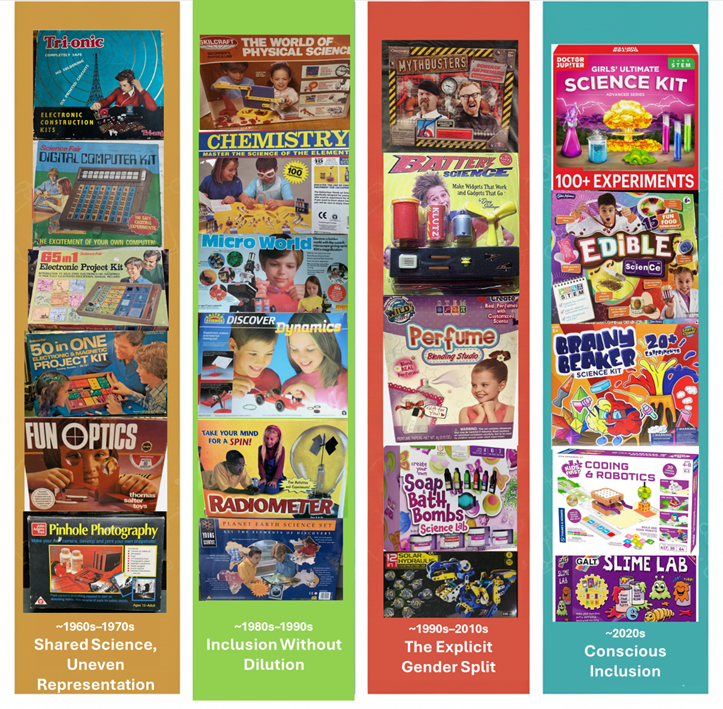

I sorted these images decade by decade, and what emerged (see Figure 2) was not the familiar, linear story of progress we often assume, but a pattern; one that helps explain why we are still campaigning about gender inclusion in STEM toys.

Figure 2: Timeline of hands-on STEM kits across six decades (1960s–2020s).

A curated selection of hands-on STEM kits marketed to children from the 1960s to the present day, organised chronologically to illustrate shifts in representation, design, and epistemic emphasis.

Shared Science, Uneven Representation

The earliest kits shown in the timeline are not gender-neutral. Boys appear alone on some boxes, girls clustered together on others, and the familiar two-point-four family on a few. The gender norms of the period are visible and unsurprising.

What matters more, however, is not who is pictured, but what the child is being invited to do.

Magnets are magnets. Circuits are circuits. Whoever opened the box encountered the same components, the same dense instructions, and the same expectation to understand how the physical world behaved.

Representation was uneven.

Epistemic access was shared.

This was not an equitable era for women in society or in science. But at the level of these toys, science itself was still framed as a single domain of knowledge. Children were not yet offered fundamentally different versions of what science was.

Inclusion Without Dilution

From the 1980s, representation broadened. Girls appeared more frequently, sometimes alongside boys, sometimes independently.

Crucially, the science itself did not soften.

Chemistry sets, electronics kits, microscopes, radiometers. Girls were shown manipulating equipment rather than observing from the side. Measurement, precision, and exploration remained central.

This period marks a quiet peak: inclusion without dilution.

Science was treated as a discipline, wide, demanding, and varied, and the kits assumed that anyone could engage with it.

The Great Gender Split

From the late 1990s into the 2000s, the timeline shows a divergence, not just in aesthetics, but in epistemic character.

A noticeable shift in many kits from abstraction, systems thinking, and open-ended problem-solving, to increasingly sensory, guided, and explicitly gendered. Pink and purple dominated the girls’ STEM toys, with hearts replacing scientific symbols. While boys got to play with electronics and robotics, and have messy hair.

The My Fantastic Fragrances kit (shown in Figure 3) is a clear example of this shift. It involves real chemistry, and cultural reference points can be powerful hooks into science. The fizz, the scent, the transformation can be genuinely engaging.

The issue was not the activity itself.

The issue was what followed.

For many learners, these experiences were treated as endpoints rather than entry points. The curiosity sparked by making a waxy, oily mixture AKA lip balm, was rarely extended into deeper exploration. Instructions and imagery signalled to girls and boys that there was one type of science for them, and what they were expected to produce, create, and complete.

Failure was minimised.

Exploration halted.

This mattered. These early encounters, without the messiness of science, shaped expectations of how science works and how failure is interpreted. It took away the complexity and ability to be curious and explore with these small boxed kits.

“My Fantastic Fragrances” Perfume Maker Kit (c. 1997).

A late-1990s girls’ science-adjacent kit, marketed through pink and purple branding and focused on producing a finished cosmetic product. While involving basic chemical processes, the activity is highly guided and outcome-oriented, reflecting the period’s shift toward gendered STEM play centred on aesthetics and completion rather than open-ended experimentation.

Where the Pipeline Really Begins

Long before learners choose subjects, qualifications, or careers, they encounter signals about what kinds of thinking feel available to them. Research on STEM participation, including work on STEM capital, shows that these early experiences shape confidence and aspiration well before formal choice points appear.

The STEM pipeline does not begin with subject choices or career guidance. It begins much earlier. In small boxes on toy shop shelves.

Redesigned Belonging — But to What?

By the 2020s, overt gender segregation in toy aisles had become far less socially acceptable, in part due to the work of campaigns such as Let Toys Be Toys and sustained advocacy from figures including Dame Chi Onwurah. Explicit “boys’ toys” and “girls’ toys” labelling has been increasingly challenged, though it has not disappeared entirely (see Figure 2). That progress matters.

However, inclusion is not only about who is invited in. It is also about what they are invited to engage with.

Many contemporary STEM kits, not all, but many, are still designed around highly predetermined outcomes: this is what it should look like when you are finished. The emphasis is on completion rather than exploration, correctness rather than curiosity.

Designing for gender inclusion or gender neutrality should not come at the expense of scientific challenge. Challenge has never been the primary barrier to children engaging with STEM. When inclusion replaces depth with simplification, it misunderstands the problem it is trying to solve.

For those of us designing systems, in education, design, manufacturing, or leadership, the question is no longer simply who feels included. It is what kinds of thinking we are making accessible, and to whom.

Inclusion without access to complexity is not equity; it is containment. If we are serious about widening participation in STEM, we must look beyond representation and attend carefully to the epistemic invitations we extend.

Final Thoughts

This exploration began as a question about gender and representation, but it ultimately revealed something deeper: many of the STEM toys and learning experiences we now offer children, while gender neutral, no longer invite them into the full joy of science; its exploration, its curiosity, its what ifs, its how does this work, and its permission to try, fail, and try again.

Luckily, there are spaces where children of all genders are trusted with the full breadth, messiness, and complexity of science. Informal learning environments such as science centres, workshops and makerspaces. These examples matter because they show that inclusion and complexity are not in tension.

But toys still matter, perhaps more than we acknowledge. Because, for many children, a STEM kit is far more accessible than a day trip to a science centre that requires time, travel, and money. A single kit, opened on the living room floor and returned to again and again, may be a child’s primary encounter with science as something they are allowed to touch, test, and take seriously. Toys are not trivial, they are often the first place where a child learns whether science is something they are welcome to linger with.

For me, as an eight-year-old with that chemistry set, the trust was implicit. I was not offered a “girl’s version,” nor a tightly scripted activity designed to arrive at a predetermined result. I was offered science. That was enough to plant a lasting sense that this was something I could belong to, because it assumed I belonged there from the start.

Author Spotlight

We’re so grateful to Authentic Learning Systems for allowing us to share her story here on Code Like A Girl. You can find her original post linked below.

If you enjoyed this piece, we encourage you to visit her publication and subscribe to support her work!

Recommend a Woman in Tech Today

Most people assume great writing rises on its own.

It doesn’t.

We are on a mission to increase the number of women on the Technology Best Sellers and Technology Rising Lists on Substack. Right now, the list contains roughly 10-13% women. We would like to see that number at 50%.

On Substack, recommendations are the distribution layer. They decide who gets surfaced, followed, and paid attention to.

We’ve subscribed to over 280 women writing about tech, AI, and robotics.

In roughly one-third of recommendation lists we see, women don’t appear at all.

Consider recommending a woman or non-binary person on Substack today.

Join Code Like a Girl on Substack

We publish three times a week, sharing technical tutorials, personal stories, and leadership insights from women and non-binary technologists.

Since 2016, Code Like a Girl has amplified over 1,000 writers and built a thriving global community of readers.

What makes this space different is that you’re not just reading stories, you’re joining a community of women in tech who are navigating the same challenges, asking the same questions, and celebrating the same wins.

Subscribe for free to get our stories, or become a paid subscriber to directly support this work and help us continue amplifying the voices of women and non-binary folks in tech.

Story References

Sweet, E. (2014). Toys Are More Divided by Gender Now Than They Were 50 Years Ago. [online] The Atlantic. Available at: Toys Are More Divided by Gender Now Than They Were 50 Years Ago - The Atlantic

Onwurah, C. Morris, A., Hutton, S. (2025) A Short Conversation with Dame Chi Onwurah - STEM, Diversity and Social Impact STEM Conversations podcast

Let Toys Be Toys Campaign (UK).

Image sources and limitations.

Images were collected from publicly accessible online listings (primarily eBay) of vintage and contemporary STEM kits. They are reproduced here for the purposes of commentary, critique, and scholarship, under principles of fair use. Dates have been inferred from product information, packaging design, and seller descriptions and are accurate to the best of the author’s knowledge; however, some approximations or minor inaccuracies may remain. The figure is intended to illustrate patterns and trends rather than provide a definitive product history.

Thank you for this wonderful post. I grew up in England (sorry!) in the 1980s and also remember that chemistry set. When I look for similar activity sets and toys for my two young girls, at the moment they all seem to be gendered around science experiments for perfume making or science experiments for girly magic and stuff like that, which just seems very strange. Thank you for highlighting why we need this to stop.

This articl is incredibly insightful. The distinction between representation and epistemic access really hits different when you look at those toy timelines. I never thought about how "science for girls" kits traded complexity for aesthetics, but looking back at stuff I played with it makes total sence. The "inclusion without dilution" framing is something every designer should internalize.