When Technology Doesn’t Speak Your Language

How AI language models quietly reinforce Western norms and leave other voices out

A note from the editor:

We’ve been following Daria’s writing for a while and continue to be amazed by her insight and curiosity. Daria is a high school student, yes, you read that correctly, a high schooler, already exploring the complex intersection of culture and technology.

She represents the future of women in tech, and we wanted to support her in every way we could. So we invited her to share the ideas behind her academic paper, Technocultural Hegemony: What Role Does Natural Language Processing Play in the Reinforcement of Dominant Cultural Narratives? in plain language for our community.

What she’s uncovered about language, bias, and AI is eye-opening and a reminder of why diverse perspectives in technology matter more than ever.

, founder of Code Like A Girl.

The New Language of Power

In the three years since ChatGPT was first introduced, language models have become an engine behind many daily tasks for people around the globe. Just like the internet years ago, natural language processing, aka NLP, is rapidly changing how we communicate. Language models shape how we perceive information, what beliefs we form, and which decisions we make. Prompt by prompt, they quietly define what “normal” sounds like.

Living Outside the Default

I experienced how technology “reinforces dominant cultural narratives” long before I knew what any of these words meant. This influence is not something we can see directly. It’s hard to define, but everyone not from an underrepresented background has probably experienced it before. It’s the occasional, barely noticeable, yet persistent reminders that technology is designed for someone else’s worldview, not yours.

I went down a rabbit hole trying to understand and articulate this phenomenon, which led me to write my paper, “Technocultural Hegemony: What Role Does Natural Language Processing Play in the Reinforcement of Dominant Cultural Narratives?”

The Cultural Impact of AI Bias

It’s no secret that AI is heavily biased towards Anglocentric views. Many studies show how language models fail to account for linguistic and cultural nuances when operating outside of Western, English-language contexts. However, the vast majority of studies test the performance of individual models and only briefly mention the broader implications of these biases.

My paper aims to bridge this gap, building on such studies to understand the broader implications of NLP for marginalized languages and communities. The analysis focuses on two key concepts, technoculture and cultural hegemony, hence the title of the paper.

Understanding Technoculture

To understand how technology and culture intertwine in NLP, I used the concept of technoculture proposed by Lelia Green. Her interpretation of the term is specific enough to use as a lens for critical analysis, and at the same time leaves enough room for new technologies.

Here are a few key characteristics a technoculture should have, according to Green:

It is in a high-tech domain;

It’s “imbued with communication and culture”;

It enables “technologically mediated communication of cultural material”;

It can negate the effects of space and/or time.

A few examples of technoculture Green uses in the paper are languages, books, and the internet. “High-tech domain” is a box that NLP easily checks. Now let’s look into the next criterion.

When Data Becomes Culture

First, NLP tools are trained on a massive corpus of human-produced texts. This data (books, web pages, social media posts, etc.) isn’t a neutral representation of language. It’s a direct product of human culture, and the biases, values, and worldviews woven into it will also be woven into the tools trained on this data. As a result, the narratives in the training corpora will influence the tools’ outputs, creating a circulation of biases and prejudices.

This study conducted an audit of Bengali sentiment analysis tools, finding that most of the tools exhibit bias towards certain genders, nationalities, and religions. These results prove that the post-colonial prejudices present in the training data tend to reappear in the tools’ output.

Second, some forms of NLP, such as LLMs or machine translation tools, involve the generation of language. They don’t simply reflect existing culture, but also produce new text material informed by human knowledge.

For example, suppose you prompt an LLM to write an email to your professor asking for a deadline extension. In that case, the model will most likely craft a polite and professional-sounding letter, even without being explicitly asked to make it formal.

This input is influenced by the norms of communication in professional settings; in turn, it may reinforce the users’ understanding and acceptance of these norms. In such scenarios, the LLM takes part in culture communication.

Machine translation tools can also facilitate communication across languages. However, they don’t always communicate linguistic nuances successfully, as I explain later in this paper.

Time, Change, and the Static Mind of AI

Another characteristic of a technoculture is the ability to negate the effects of space or time, which manifests in NLP in quite an interesting way. The training corpora only represent a given moment in time, but human culture evolves continuously, with values and norms changing over time.

Since NLP tools don’t currently learn in real time, their model of reality is static, so it only represents a snippet of culture at a given moment in time. Books are a suitable analogy; a book written in the 19th century will always represent the values of the 19th century, regardless of when it’s being read. Although models get replaced very quickly, a model from 2018 would likely have a slightly different “understanding” of the world than a model trained in 2025.

Based on this short analysis, it makes sense to believe that NLP can indeed be considered a form of technoculture, and that its cultural elements can’t be separated from its technical aspects. We can see how language modelling isn’t just a technique, but a space where technology and culture coexist and influence each other.

Cultural Hegemony in the Age of AI

The concept of cultural hegemony was first introduced by the Italian Marxist philosopher Antonio Gramsci. It explains how the ruling elites maintain their supremacy in society by establishing their values and ideals as the default, or “common sense”, via social institutions. Unlike traditional power acquired and maintained through force, this kind of dominance relies on the more subtle control of cultural norms.

Originally, Gramsci used the concept to describe how the ruling class in a capitalist economy maintains its dominance over the working class. Over time, the term was extended to mean, more broadly, a dominance of one cultural group over others. It is especially relevant now that, with the advances in technology, cultural hegemony can transcend geographical boundaries.

I chose cultural hegemony over other potential theories because it encompasses perfectly the way Western culture positions itself as a universal norm, not through colonization or “globalization” (although these factors do play a role), but through subtle, barely noticeable means.

This part of the paper focuses on two specific types of cultural hegemony: the westernization of cultural defaults globally and the hegemony of English as the universal lingua franca.

As I’ve mentioned before, many studies show that NLP tools, especially LLMs, display some degree of bias based on factors like gender, nationality, religion, race, and other identity dimensions.

When English Becomes the Default

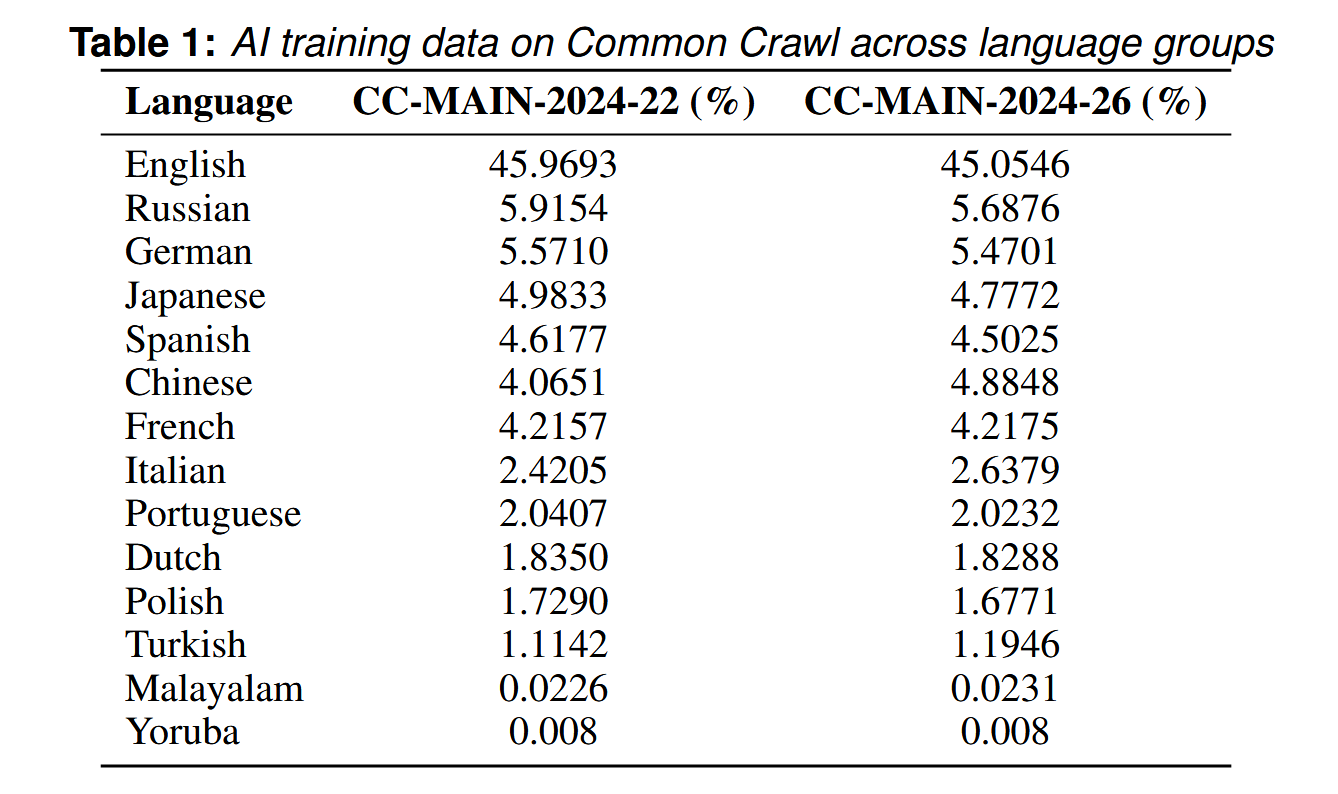

The primary source of these biases is the training data imbalance. Unlike English, the majority of the world’s languages aren’t adequately represented in the training corpora.

For example, on Common Crawl – a popular source of training data – 45% of the corpora is in English. The figure below shows the percentages of corpora for selected languages. Given this skew, it’s not surprising that language models tend to uphold the values of the English-language communities disproportionately.

Another critical factor is the availability of pre-trained models. Fine-tuning an existing model is way less costly than training one from scratch, but pre-trained models only exist for relatively few languages.

As a result, NLP innovation is almost always centred around English, because there are simply more resources to work with. New tools are often first introduced in English, and only later adapted for a few other languages. This gives the English-speaking world a significant advantage, while speakers of low-resource languages are excluded from the newest developments and their benefits.

However, disparities persist even when a model nominally supports multiple languages. According to this study, multilingual models’ performance in low-resource languages tends to be worse than when a model only supports that language. So even if low-resource language speakers can technically use the tool, they are still at a disadvantage compared to high-resource language speakers.

To explain this problem, a group of researchers introduces the term “language modelling bias”. They define it as a situation when

“the technology, by design, represents, interprets, or processes content less accurately in certain languages than in others, thereby forcing speakers of the disadvantaged language to simplify or adapt their communication, (self-)representation, and expression when using that technology to fit the default incorporated in the privileged language.”

This is a classical example of how people whose experiences don’t fit into the established cultural “default” have to code-switch and adapt their self-expression in order to be understood.

The Illusion of Inclusion

The nominal “inclusion” at the expense of true representation is caused by the oversimplified idea of diversity in the field. The tech world often sees inclusion as a box to check, not a guiding design principle.

Western developers often fail to account for some languages’ nuances that can’t be directly mapped onto an English equivalent. This sometimes results in absurdities.

For example, in Hungarian, there is no direct equivalent for the word “brother”. When translating the sentence “my brother is three years younger than me”, Google Translate would output “A bátyám három évvel fiatalabb nálam” - which literally means “my elder brother is three years younger than me”.

Such a “top-down” approach harms native speaker communities more than it benefits them, by forcing them to fit into the Anglocentric standards of communication to be understood by the technology. This creates an illusion of representation, while in reality, it further marginalizes those whose forms of self-expression don’t neatly fit into the Western standards, which the technology positions as universal.

When Words Can’t Hold Our Worlds

The study that introduces language modelling bias also references the concept of hermeneutical injustice. It’s a situation where someone’s experience or reality isn’t understood or represented, because the means of expressing it simply don’t exist. In this context, hermeneutical injustice describes the exclusion of people whose language isn’t adequately represented by NLP technologies.

Language is perhaps the most common way for us to express ourselves; Gramsci acknowledged that “every language contains the elements of a conception of the world.”

When people have to adapt their language to be able to interact with technology, their experience gets filtered through the Anglocentric lens, and their very “conception of the world” gets lost. Such a form of systemic underrepresentation serves to promote Western values, norms, and views as a universal standard that everyone has to adapt to, while sidelining alternative perspectives.

Technology as a Cultural Medium

The real point of this piece was to show how NLP isn’t just a technology — it’s a cultural medium. Like most other technologies, it can end up reinforcing the stories and power structures that already dominate our world. I hope that this work also makes a case for building technology with communities, not just for them, because “innovation” imposed from Silicon Valley often misses, or even harms, the people it claims to serve. As NLP tools spread around the globe, we need to make sure they’re not just amplifying the same few voices while leaving everyone else out.

Author Spotlight

We’re so grateful to

or allowing us to share her story here on Code Like A Girl. Here is the note where we discovered Daria had written an academic paper!If you enjoyed this piece, we encourage you to visit her publication and subscribe to support her work!

Join Code Like a Girl on Substack

We publish 2–3 times a week, bringing you:

Technical deep-dives and tutorials from women and non-binary technologists

Personal stories of resilience, bias, breakthroughs, and growth in tech

Actionable insights on leadership, equity, and the future of work

Since 2016, Code Like a Girl has amplified over 1,000 writers and built a thriving global community of readers. What makes this space different is that you’re not just reading stories, you’re joining a community of women in tech who are navigating the same challenges, asking the same questions, and celebrating the same wins.

Subscribe for free to get our stories, or become a paid subscriber to directly support this work and help us continue amplifying the voices of women and non-binary folks in tech. Paid subscriptions help us cover the costs of running Code Like A Girl.

You did a wonderful job on this article, Daria!

You continue to impress me with both your writing and your coding skills. You’ve highlighted a major disconnect emerging as AI rolls out. It feels like a passenger train speeding down the track without stopping at any stations — the only passengers are the ones who were already onboard when it left.

You mentioned the idea of “checking boxes,” and that captures the feeling perfectly. It’s hard to understand how this is going to change. If you don’t accept what’s being built out right now, you risk being left behind. But on the other hand, perhaps once one or two AI models become dominant, there may be room for real improvement and accessibility.

It reminds me a bit of the 90s, when multiple search engines were fighting for the top spot. In the end, Google took the crown, though Yahoo put up a strong fight for a while.

Keep up the great work, Daria — and congratulations on being featured on Code Like a Girl.

This is a hefty topic! I can imagine how much knowledge you actually have on the topic and how much you've had to pare back for purposes of Substack.

You bring up multiple great points - my favourite: "When people have to adapt their language to be able to interact with technology, their experience gets filtered through the Anglocentric lens, and their very “conception of the world” gets lost."

We're now living deep in a world where algorithms are deciding how we speak in order to be heard. Social media, as you know, has created a social media speak that is now winding its way into everyday vernacular. I've recently been seeing Indian content creators comment on how their peers are changing their accents to 'fit' into Western concepts of 'content creation'. That kind of erosion is going to become more and more common place because of all you explored here.

These shifts over time have buried us deep in a human-machine dynamic that is fascinating, and important to take stock of, especially as we deal with large language models - how we influence it, and how it influences us right back. A terrifying loop of language modelling.

There aren't a lot of female linguists that get talked about, they're mostly stodgy, old white men - BUT! Deborah Tannen is my personal favourite, I think you'd really like her work.